Turn your Google Spreadsheets into JSON without doing anything!

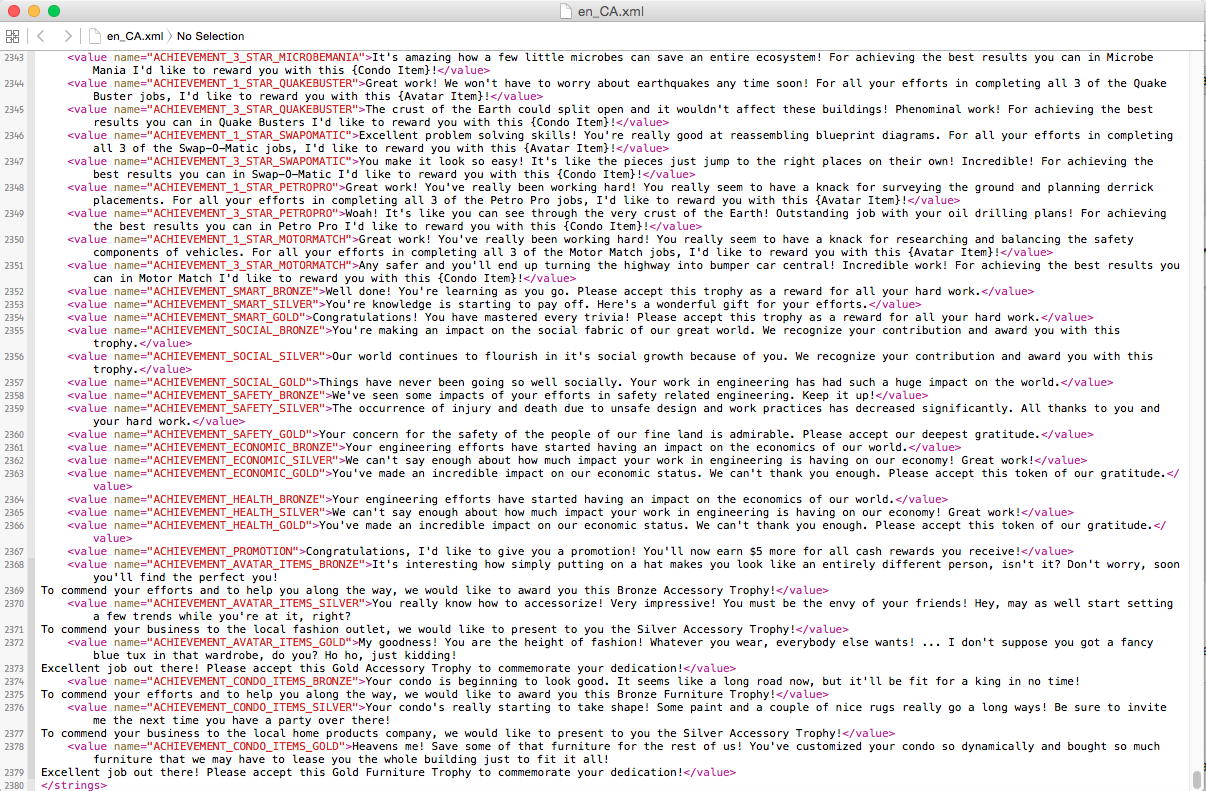

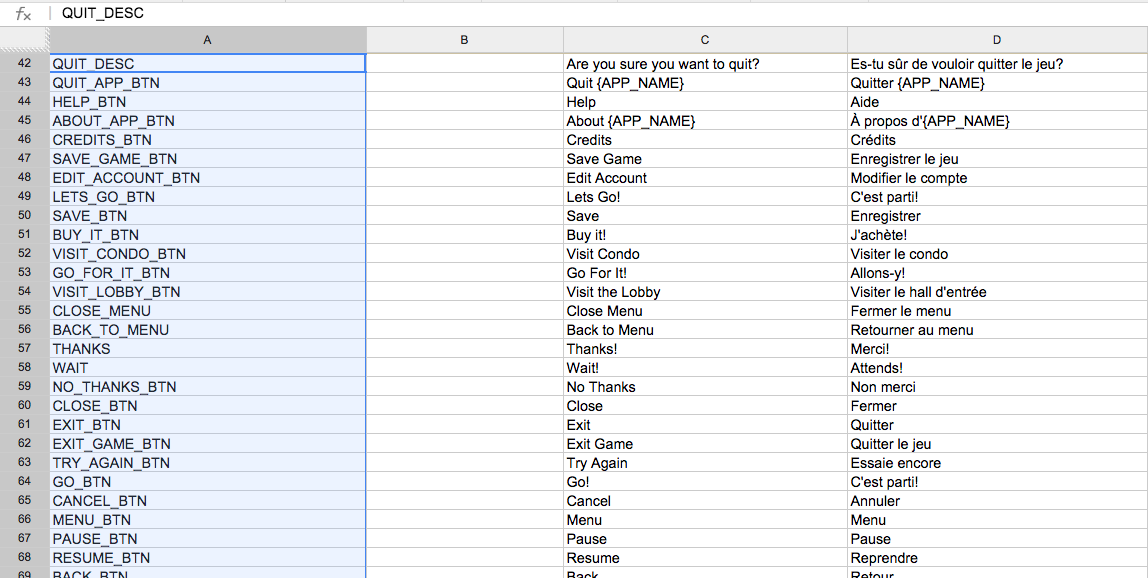

A while ago, I did a Flash project that was fairly heavily text-oriented. To help keep track of all the text, all the strings were given labels and placed in a JSON, spanning about 1500 lines and calling almost 4000 different references all throughout the code.

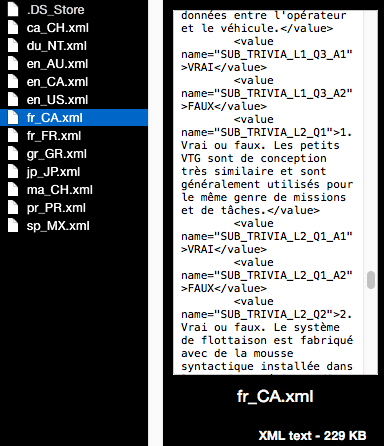

Later on down the road, the client contacted us and told me that they wanted the language of the strings in English and in French. Alright, no problem, just have to manually update these 4000 references and run checks to see what language is being used … no, ain’t happening like that.

Instead, because we referenced all this text from a JSON initially, all I had to do was simply set it up so that if the user wanted french, the program simply loads up a french JSON with all the same labels; just with different content. Simple.

Enjoy the next three months of your life!

… yeah, not really. 2400 lines! Gotta make sure they’re not only all labelled the same as each other, but they also need content. Otherwise, if the strings aren’t found, the app will either throw errors and display “undefined” all over the screen, or show a bunch of locale keys. And what do we do if we decide to add new strings, or remove unneeded ones, or ([insert deity here] forbid) rename existing ones? We would have to check and change both JSONS, hunting down the strings in each, and pray that the client didn’t decide the app should also be in Spanish.

Ohh nooooo!

A scary-sounding prospect, but it was solved by some luck and somebody thinking ahead.

Initially, before creating the JSON, we were storing the strings on a Google spreadsheet for reference. Column 1 had the labels and column 3 had the strings (column 2 had descriptions). Because the spreadsheet was online, both myself and the client were able to check up on the file and make changes at the same time.

Ahh! Much better!

We also created a little algorithm using an earlier Google spreadsheet API that saved the spreadsheet on demand and converted it into a JSON. Bit of a convoluted process at the time where I had to call an “update” option, wait a few seconds, and then download the JSON file using an FTP link, but it was still much better than manually changing the JSON by hand.

Revisiting the Process

About a year later, I was asked to revisit this. We had another project in the works that used this same sort of format, and I was asked to see if there was a way to use this script to create a JSON of the spreadsheet on demand. Not only that, but my code should also be universal so it could be referenced or even copy/pasted into other spreadsheets. Fun!

Now, a regular worker would just look at the old code we originally used and copy/pasted that without a second thought. I mean, if it works, why change it? That’s fine and all, but I was more interested to see how the process worked. I wanted to create my own version of this code, up to date with the latest frameworks. Perhaps I could even create a more optimal or flexible version of it. And I was given a week. So let’s do it!

Let’s start with the basics. As it turns out, Google Spreadsheets has a script editor that allows you to run code directly on the spreadsheet, either on demand or in response to an event. Sounds good, but what caught my attention was “response to an event”. Apparently there was code that ran simply from the action of opening the spreadsheet and modifying a cell. I investigated and found that there were only 4 available events, but they were considerably powerful nevertheless.

For example, if somebody opens the spreadsheet, an event called onOpen is dispatched within the script. Via a listener, I could get a reference to the user’s name and date and add a log stating who modified the spreadsheet, and at what time. And then store it on said spreadsheet because I can.

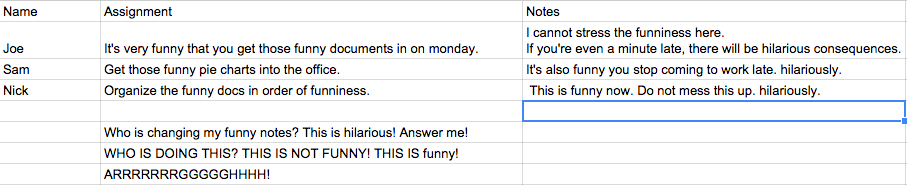

It gets better. There is also an event called onEdit that runs a script whenever a cell block is changed. I could use that to run an auto-format script that capitalized the first word, ran a spell-check algorithm, or even censored bad words. And this would happen automatically. No pushing buttons or clicking switches. Heck, the poor user didn’t have a choice, because this code would always run when a cell was changed.

function onEdit(event) {

sheet = SpreadsheetApp.getActiveSheet();

var edittedCell = sheet.getActiveCell();

var edittedCellContents = edittedCell.getValue();

edittedCellContents = String(edittedCellContents).replace(/important/ig, "funny");

edittedCellContents = String(edittedCellContents).replace(/importance/ig, "funniness");

edittedCellContents = String(edittedCellContents).replace(/serious/ig, "hilarious");

edittedCell.setValue(edittedCellContents);

}

What surprised me was that there was also a message system that allowed me to not only load files by URL using a GET message, but also write and save data to them using a POST. This was it! I could use this to create a JSON file and post it to a pre-determined address!

As you can see in the above example, this sounds like it can pave the way for some rather serious issues. A programmer could write an add-on that, hidden within his code, could take all the spreadsheet data and write it into his own file on an FTP somewhere. Wouldn’t be good if it was an add-on built to organize a company’s employee addresses and credit card numbers, eh?

Fortunately, the default triggers are limited in functionality, including writing to file. That was a relief.

Unfortunately, the default triggers are limited in functionality, including writing to file. That was a problem.

Looking more into the code, I found out that there are these default triggers, yes, but there were also manually set triggers. Triggers that you have to manually set up and authenticate through your account in order to allow. These triggers also included their own variations of onOpen, onEdit, etc. All you had to do was pick the trigger and select which function ran when the trigger was called in the editor. And they had no such restrictions!

I worked with that instead. Setting the trigger up was a one-time process anyways, and it was simple enough that I was able to write the instructions within the comments of my code.

So, I wrote an algorithm in the script that, when onEdit was called (the manually set one, not the default one), gathered data in the first column and created an array of IDs. Then for each column at, and after, column 3, I filled the strings with their matching IDs depending on the language the column used. Because it’s manual code, I was also able to add other functions to combine duplicate IDs, spell-check, and replace all instances of the word “important” with- … just kidding, boss.

// Fill the JSON full of data.

for (var elements = 0; elements < namesLength; elements++) {

// Get the name...

name = names[elements][0];

// Don't attempt to parse this row if it's empty space.

if (!name || name == "") { continue; }

// Get the data...

data = datas[elements][0];

// Add to the object.

json[name] = data;

}

With this giant array of data objects (one for each language), I converted them to a set of JSON objects. This was actually very easy because Google’s framework actually came with its own JSON-to-string converter. Saved me having to write a lot of format conversion code, which is pretty neat.

var json = JSON.stringify(jsonString);

Once that was done, I used a POST message to send it to a .php file elsewhere that worked its own strange magic to upload it to a chosen destination on my computer (but that’s another story).

// Send POST message to the file. Store JSON in "options".

UrlFetchApp.fetch("http://targetsite.com/locale/index.php", options);

Finally, we also created an on-demand system using Grunt that would automatically get the latest file straight from the dev site onto our local system, which skipped the step of having to download the JSON.

The Result

This meant that every time one of us updated the spreadsheet, the JSON file automatically updated on its own, and if I wanted to test the application, it would automatically retrieve the latest JSON. I didn’t have to do anything else. At all. And because the spreadsheet code was an add-on code file saved to my Google Drive, I could apply this code to more than one spreadsheet and share it with my co-workers.

Therefore, thanks to the techniques of automation in your daily workflow, we have saved a lot of development time by automating a process that would’ve otherwise taken minutes each time we wanted to run a test!

So I turned it in, got a pat on the back and a cookie, and went on to do my next project. Such is the life of a programmer; but I gotta say we get the tastiest cookies ever.