I’ve always had a complicated relationship with learning as a designer. It’s satisfying to gain new skills, but staying in my comfort zone feels so much easier. I want to push myself and get awesome results, but there’s an intimidating hurdle of not knowing how to start. The bottom of the learning curve is a scary hurdle to confront. 3D design had that hurdle stalling me from progressing. Dipping my toes into 3D modelling and quitting after a week was a common occurrence for years. There’s dozens of abandoned attempts sitting on my old hard drives. Something always prevented me from wanting to continue. Normals, modifiers, rendering — 3D felt too overwhelming and vast. I felt stumped. How do you get started learning something when you don’t even know what you don’t know?

Luckily, there is a cure for my 3D phobia. I recently joined a digital interactive agency, gskinner, who emphasizes professional development. They give dedicated time every week to learn new skills so it’s harder to make excuses. Over the past two months I have used this PD time to finally commit to learning 3D and Blender. The results so far have been modest and clumsy, and there’s a lot more to improve on. Despite the struggles, I want to share my progress and show that 3D might not be as scary and impossible after all.

Accepting I Don’t Know Everything

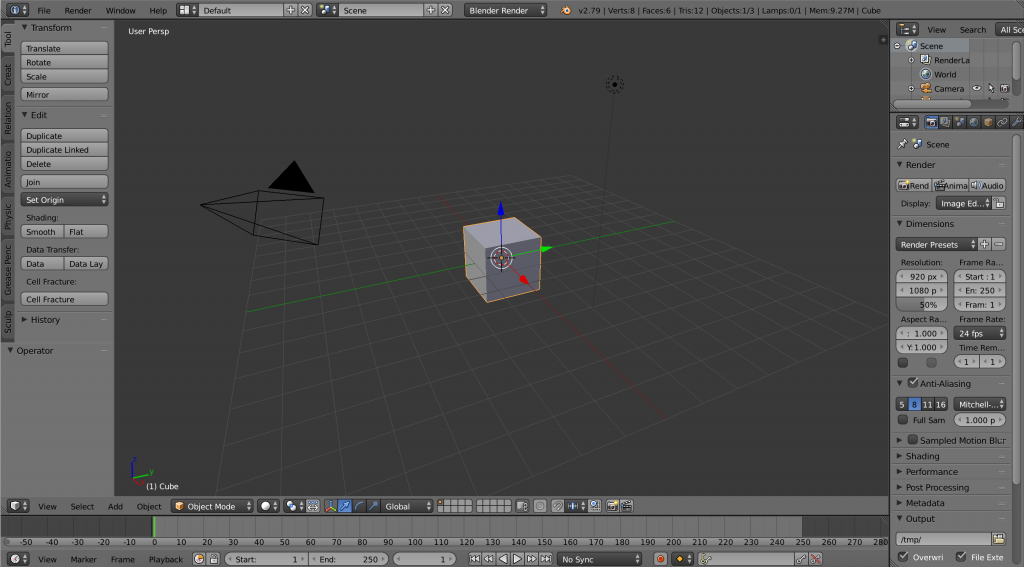

There’s nothing quite as humbling as loading up new, freshly-installed 3D software. I remember looking in horror at Blender’s interface and having no idea where to start. Gray buttons, panels and nonsensical windows welcomed me with intimidating ambiguity. What made the fear worse was knowing that my coworkers were expecting me to learn this software. I couldn’t close the window and go back to my safe, predictable Photoshop and Illustrator. I couldn’t shrug and say “3D isn’t for me.” There was no place left to hide. Looking back, this external pressure was a blessing in disguise. It became the initial push into the unknown to start something new. After years of skirting around and avoiding Blender, I had to swallow my pride and get to work.

What have I gotten myself into?

Breaking Down the Pieces

Unlike my prior attempts at learning 3D, there would have to be a deliberate approach. I would try to break down the software into chunks to reduce the sense of intimidation. Next, I would share my progress with my team members experienced in 3D. I hoped that small steps combined with feedback would make Blender seem manageable.

I kept my goals small and gradual. Learning the main hotkeys and how to navigate the software became my first objective. My second goal was to make basic shapes. I opened up my first introduction to Blender tutorial and started the journey. After hours of tutorials and fumbling with hotkeys, I learned how to move and deform cubes. My screen had become filled with dozens of scattered, warped meshes. It looked like a mess, but it also felt like progress.

The magic of extrusions and subdivisions

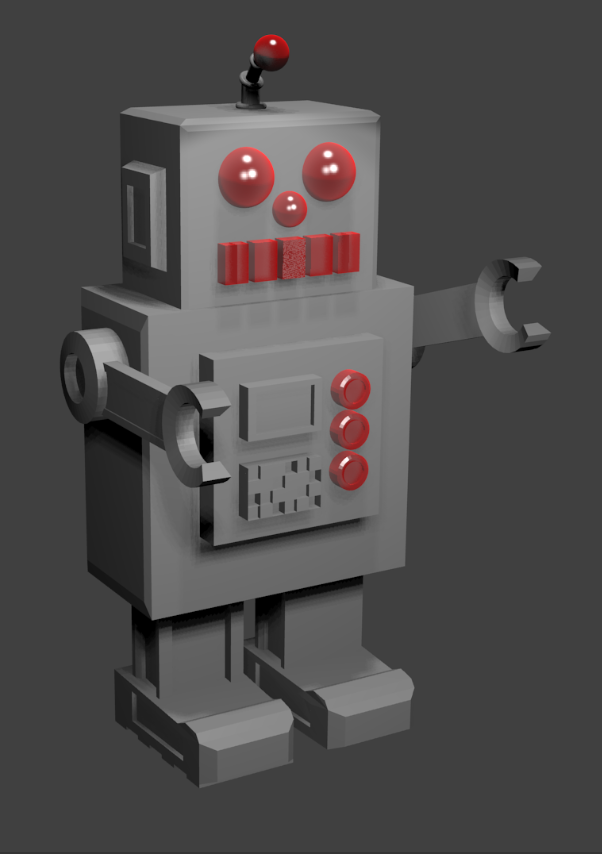

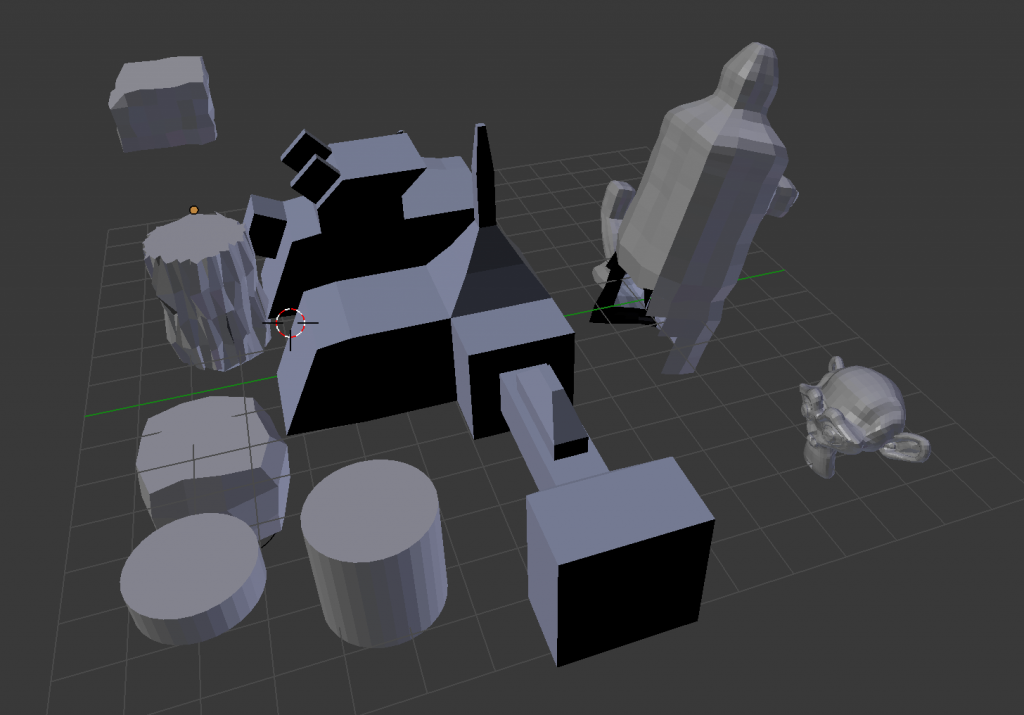

After overcoming the initial shock of Blender, the next goal was to try to make something. I gave myself a time limit of 3 hours to make anything I wanted from what I had learned from the tutorials. Not wanting to set my expectations too high, I chose to model a robot since organic forms were beyond me. This allowed me to practice basic extruding, materials, lighting, and rendering. Learned concepts started to come together as I built my robot piece-by-piece. At the end of the sprint, there was a modest little mesh I could call my own. It was encouraging to see I had made visible progress after a week of basics.

After this small success, I laid out the general method to continue learning Blender:

- Identify what to learn

- Watch tutorials of what I want to learn

- Copy the tutorial

- Practice the contents of tutorial until comfortable

- Apply the new knowledge to a small experiment

- Share the results & solicit feedback

- Repeat

If I don’t stick to this structure when learning, I tend to veer off in too many directions. Having a step-by-step process, I felt more committed to actually progress with what I set out to do. On top of that, having to share my progress with the team made me want to try to the best of my ability. There was some stake.

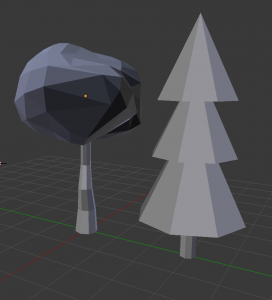

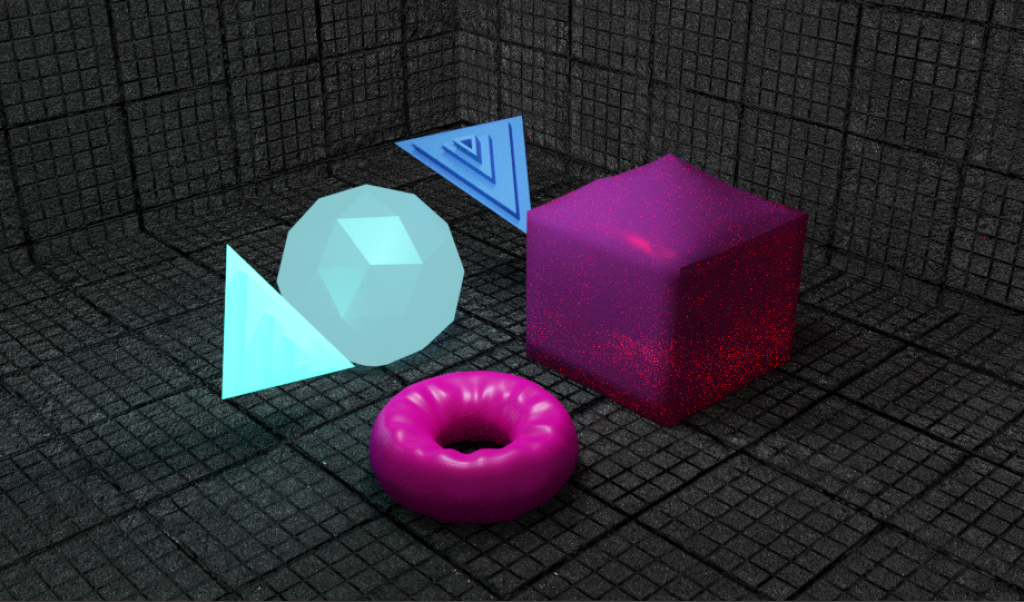

With each week I would try to add a new concept to what I had learned the week prior, and the method started to pay off. After mesh models came textures and node editing. Then came basic lighting setups and rendering. Gray cubes became trees, rocks, swords, and more. Those objects then started to have texture and colour. Lighting added a sense of realism that hadn’t been there before. Every week brought new mistakes and frustrations, but that frustration was always temporary. The satisfaction of getting something to work and come to life was well worth the struggle.

The Challenge

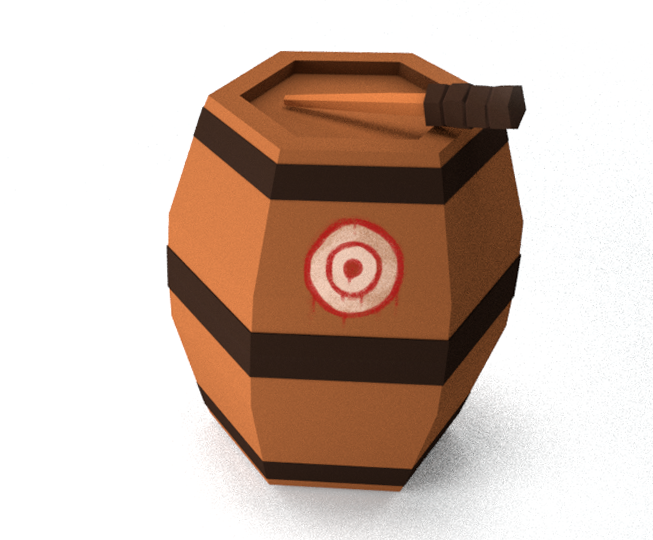

After practicing for a few weeks and grasping the bare basics of Blender, it was time for a larger challenge. The test: design, model and UV map a torch and a barrel in a low-poly style. “This should be easy”, naive me thought. I had already made prop sketches for what the models should look like, so there should be no trouble. My overconfidence got the best of me and I decided that I didn’t need to look at reference while I modelled. Big mistake. Always have your reference visible while modelling! It’s amazing how fast I could forget what my own drawings looked like when they weren’t right in front of me. Unsurprisingly, the results didn’t look like what I had expected.

A first attempt at modelling and UV mapping a barrel and torch

Another mistake was rushing into UV maps before adequately researching the subject. In my naive confidence, I thought I could figure it out as I went along modelling. The results: disorganized maps that didn’t have the proper shading or resolution. I didn’t know what baking was or how to export UV layouts, so making maps had become a guessing game. I could have avoided this mistake the first time if I had taken time to research first. Following tutorials is a faster way to learn compared to blindly making preventable mistakes.

I shared my results with the team and luckily they pointed out my errors and moved me in the right direction. That’s one of the perks of surrounding yourself with people who know more than you: it gets rid of the guessing game. I could make my mistakes faster. After more attempts and hours of practice, my models were finally completed. They’re not perfect, but they are much closer to what I was trying to achieve, when compared to the first attempt. As it turns out, a great way to learn something is to repeat the same project over and over until it finally looks good.

Climbing the Learning Curve

In this experience, the two main challenges to overcome were my pride and impatience. Before, I was too concerned about everything in 3D not looking perfect the first time around. Worse, I didn’t want others to see me making mistakes. Yet, nobody rational is going to fault you for trying and making mistakes. Learning a new skill takes time, but I was too focused on getting big results fast. I need to remember to reel myself back when I try to get too much done without the proper preparation. I could have avoided many hours of frustration and mistakes if I had slowed down and been patient.

Learning Blender has in many ways been exactly how I expected it to be: difficult, confusing, and time consuming. There are so many variables to consider and every attempt I make so far looks and feels subpar. Yet, there is one thing that makes me want to keep on chipping away at this skill: gradual, visible progress. Looking back, I can already start to see the my attempts improve over time and I’m excited to see where I go from here. Am I some kind of 3D wizard now? Definitely not. But I have made strides which have brought me closer to my goals. Marginal gains add up over time. That’s the real beauty of the being at the beginning of the learning curve; it’s only up from here.